We Have a Teacher Shortage. We Also Know How to Fix It.

January 10, 2023

January 10, 2023

By Tom Allen

VEA President James J. Fedderman would like you to know that, at its core, this ain’t rocket science. “We all know we have a teacher shortage in Virginia and the reasons for it aren’t a mystery to anyone who’s been paying attention,” he recently told state media outlets. “Our teachers are not only underpaid, but do their jobs under almost unbearably difficult working conditions. They don’t get the respect they deserve, and they aren’t given the resources they need to most effectively serve our students.”

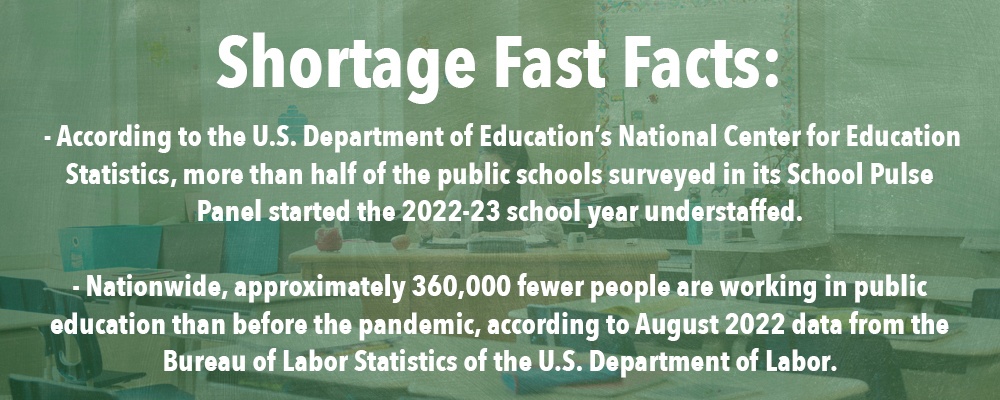

The problem is clear-cut, and the stakes are incredibly high. Fortunately, the factors in a multi-prong approach to solving this problem are equally obvious. What remains is bringing our actions and political will in line with what we claim to value.

A great place to start is at the negotiating table. One of the most direct and effective ways to put a meaningful dent in our shortage, Fedderman says, is giving teachers a role in contract negotiations. “If the new collective bargaining law for school employees that we helped get passed was in place widely around our state,” he notes, “educators and local school leaders would be negotiating effective ways to fix teacher shortages in their communities.”

A recent study backs VEA’s position that this would be a good move for everyone. The Commonwealth Institute, a Richmond-based think tank that advocates for racial and economic justice in public policy, issued “Collective Bargaining: A Critical Tool to Improve School Staffing, Pay and Morale,” in October. After presenting evidence that contract negotiations boost teacher and staff pay, improve working conditions and morale, help build retention and, on top of that, are good for student achievement, the report concludes, in part: “Our public education system’s most valuable resource – its people – has long been forced to do increasingly more with increasingly less. And the COVID-19 pandemic has deepened the strain on teachers and school staff. Collective bargaining is a critical aspect of how to correct this dynamic…It is time for all local school boards to support teachers and school staff by permitting them to collectively bargain.”

Virginia’s collective bargaining law for public employees requires local unions and school boards to jump through a number of challenging hoops, however, so the process for having negotiations in place around the state is an ongoing and lengthy one.

What’s also been a far-too-lengthy process is making payday a better and more deservedly-happy day for our commonwealth’s teachers. Here are a couple numbers that are surely a major factor in our current shortage: Virginia’s teachers are currently paid an average salary of $58,506, which translates to $6,787 less than the national average salary for teachers. That’s over 10 percent less than the national average, in a state that has consistently offered one of the country’s best systems of public schools—and a state with the financial ability to do far better.

That’s inexcusable.

“Far too many of our educators, both teachers and support professionals, must work second and third jobs to pay their bills,” says Fedderman. “We say that education is an extremely important profession, the one that makes all others possible—but what other profession has to do that? When’s the last time you saw a lawyer waiting tables part-time? When educators spend time and energy at additional jobs, students are shortchanged.”

Research shows (though common sense seems sufficient) that better pay and benefits go a long way in helping attract the best and the brightest. And don’t we want the highest-quality individuals we can find at the front of our classrooms?

Seeing one’s vocation as a calling, as many teachers do, is a wonderful and fulfilling thing. Why do we expect people who follow their calling, or choose their career because it’s something they love, to do so at such financial sacrifice?

Incidentally, research also shows that effective teachers are the single most important factor in students’ academic success. Doesn’t it make sense to invest in them?

“We’ve always said that teacher work conditions are student learning conditions,” says Fedderman. “When you improve one, you automatically improve the other.”

And there is lots and lots of room for improvement in the working environment for teachers. Some of the primary factors in a teacher’s work world are teacher and school

leadership, educator voice, community support and parent engagement, time for teaching, class size and caseload, student conduct, physical and cultural environment, professional

learning and collaboration, and assessment cultures, according to the National Education Association. Here are some much-needed steps to create an atmosphere that will pay off for both students and educators:

When the Great Recession hit in 2009, one of the steps legislators took to save money was the “support cap,” a change to our school funding formula that significantly limited the number of support professionals school systems could hire. While this strategy may have been helpful during that emergency, a decade later it’s contributing to our teacher shortage.

“Since the massive cuts to support staff positions, teachers have had to wear more hats than ever,” says Chad Steward, a VEA policy analyst. “They’re counselors, nurses, librarians, custodians, you name it. Those kind of support positions are mission-critical to schools. No wonder teachers are burning out faster than ever.”

Doing away with the support cap would do two very important things: Bringing in more support professionals would allow teachers to focus on what they do best—teaching, thereby reducing the pressure we’ve put on them, and the increase in state funding would free up local dollars, allowing them to help pay teachers what it takes to attract and retain them.

Our teacher shortage, sadly, is often felt most in the areas where we most need excellent teachers. “Teacher vacancy rates are twice as high in our highest poverty school divisions compared to our lowest poverty divisions,” says Stewart.

Again, it’s not rocket science: “Virginia doesn’t come close to providing our highest-need schools with the resources to serve all students,” says Stewart, leaving teachers in those schools with nearly insurmountable challenges. “Our school funding formula leads to many high-poverty school divisions having among the lowest per student funding levels. This is upside down from what education experts say is needed.”

The best option in our state budget to correct this is the At-Risk Add-On, which ties state support to schools based on the share of low-income students. Without a major funding boost to this mechanism, which would allow high-poverty schools to better hire high-quality teachers, inequities will only grow—and so will teacher shortages.

We know that many of our students face significant barriers to academic success because their basic needs aren’t being met. We also know that community school models are effective in breaking those barriers down. A community school is set up to offer wraparound health services, before and after school learning opportunities, coordinated family and community engagement, and can also use existing local, state, and federal resources to create even more services based at the school.

“Across the nation, community schools are being looked at to bridge the gap between what students are getting and what they need,” says Amber Brown, VEA’s Teaching and Learning Specialist. “This benefits everyone—students, families, educators, and community stakeholders. The NEA has been a strong advocate for this work and provides support and assistance for states that are having these conversations.”

Community schools, in addition to going a long way in helping more at-risk students succeed, would also be effective shortage-fighters: When students are free to learn, teachers are free to teach, leading to better outcomes for everyone. Community schools are a savvy investment for our legislators to consider.

Every two years, the Virginia Board of Education revises the state’s Standards of Quality, which are essentially the minimum conditions for providing a quality education to our young people. And just about every two years, the General Assembly fails to fully fund those standards. The SOQs represent the thinking and research of some of the leading K-12 education experts in our state and beyond.

“The SOQs are an essential guide in helping our public schools become all that they can and should be,” says Brown. “When we don’t fund the recommendations made by our state’s school board and other vested educators and stakeholders, it comes across that public education is not the priority many claim it is.”

Again, while funding the SOQs may not seem to have a direct effect on our teacher shortage, it would enforce items like the counselor-to-student ratio, funding for students who must learn English, and a lineup of important support positions and programs in our schools—all steps that will make life in the classroom a lot more appealing to current and potential teachers.

Allen is the editor of the Virginia Journal of Education.

Some approaches that won’t help, but are still very much in vogue in some places:

Make it easier for the under-qualified to get into teaching.

Undermine public trust in and respect for teachers.

Act like it’s not a real problem.

Virginia is a top 10 state in median household income, but ranks 36th in the US in state per pupil funding of K-12 education.

Learn More